"Catastrophic Years"

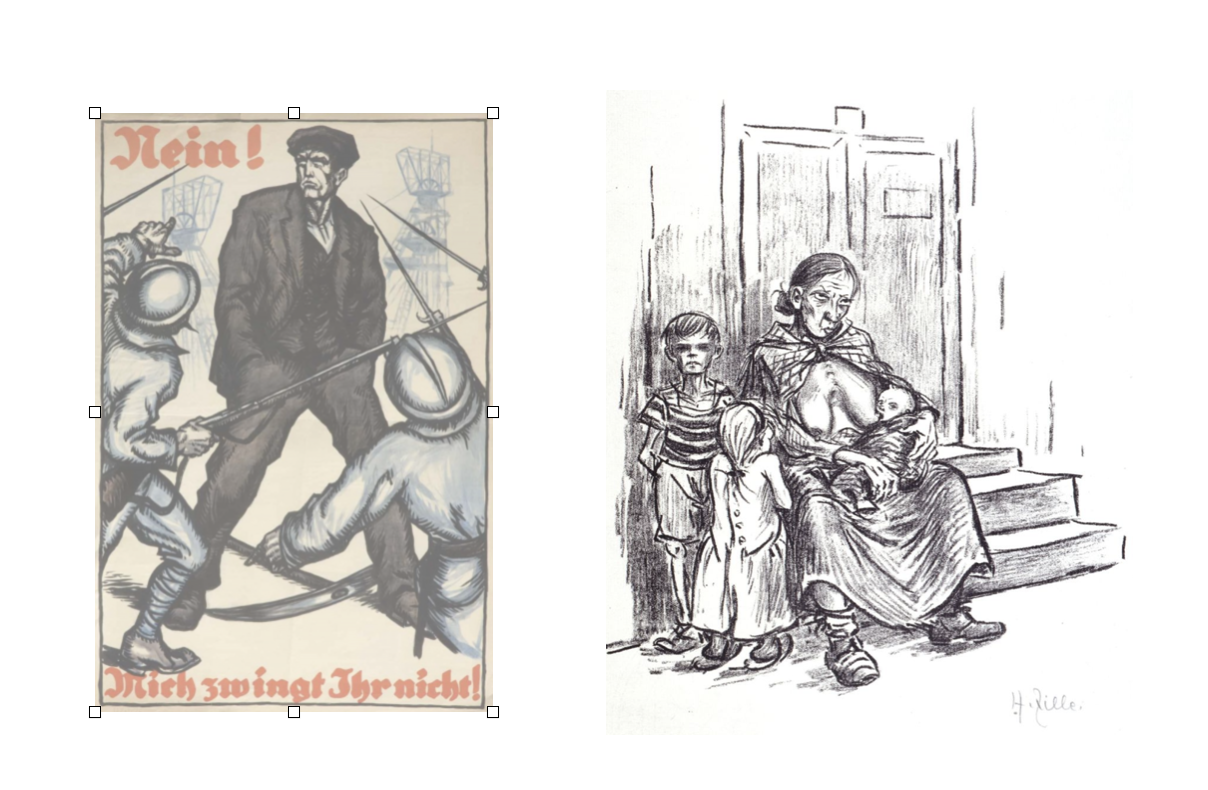

Shortly after the first world war and an equally devastating pandemic for all, solely the German nation would plunge into another era of catastrophes. What happened?

Indeed, this characterisation may not necessarily come from any designated author of historical-political reputation. A German philosopher produced it. And of course, naming 24 successive months as "catastrophic" is an intriguing statement from the historical perspective. Regarding the contemporaries that we are looking at a hundred years later on, how many Germans would have been able to sense that years of catastrophe were awaiting them – being the tragic subject of the Paris/Versailles diktat? Though this diktat's evil premises were unprecedented and implied an even more unprecedented nemesis of its own.

Obviously, Brexit England is ahead of all others in demonstrating unawareness of these history lessons. At some distance from Great Britain's exit from the European Union, the increasing and, most notably, bipartisan critique from Englishmen centres on the economic consequences. In contrast to this ostensibly national perspective, less visible, long-term political implications, which more or less applies to other Europeans as well, are being ignored. What about the ongoing research into isolated Russia's supporting the Brexiteers' campaign? Not to mention the Russian–atlantic Alliance proxy war in Ukraine. Of course, on the English side there is other voices on offer, such as historian Neil Gregor's, Declassified UK or Pink Floyd's Roger Waters.

As a matter of fact, taken away from Germany's national perspective, I would plea for a new historiography that revaluates George Kennan's analysis of the late 1970s. It sees the First World War, most notably adapted to the 1914 – 1919 parameters (as a contrast to the "military variant" of 1914–1918) as the seminal catastrophe of the twentieth century.* Besides that, the thesis of the second "Thirty Years' War" (1914–1945) may come to the fore. Apart from this plea, our mission is to provide access to forgotten anniversaries of the first post-war period and to pioneer a comprehensive culture of memory.

"Katastrophenjahre" 1922 and 1923, Wolfram Eilenberger (2018), Zeit der Zauberer. Das große Jahrzehnt der Philosophie 1919-1929, Stuttgart, p. 146.

The day before Christmas 1921, German President Friedrich Ebert repeals the "Verordnung zum Schutze der Republik (Ordinance for the Protection of the Republic)". This concludes the state of emergency.

Nobody seemed to have anticipated a catastrophic year, let alone two of a kind.

Surely, determinism is what we would like to forego at all times. The course of history could have gone differently. More than the highly afflicted Weimar democrats obviously, their established colleagues in France and Great Britain have not only had policy alternatives in Lausanne, in Geneva and Locarno. Over more than twelve years, much more than paying lip service to revisionism could have taken place as much as novel agenda setting for constructive peace-building.

1922 was a post-pandemic year for all nations that had lost millions to the Spanish Flu. From Germany's national perspective, much more than two revolutions and this pandemic preceded the dawn of this fourth postwar year.

- Two years before, on January 10, 1920, the punitive and demoralising Treaty of Versailles had been put into force.

- The Weimar democracy had been told half a year before (1921, link) how many billions actually were stated on the reparations bill. There was no misunderstanding that several generations would have to labour in order to meet the obligations.

What actually happened as a consequence of these positions and beyond in 1922 ⎼ 1923? This Aufa100 blogpost will be updated a few times. Follow us on LinkedIn.

* P.S.: Most notably, the German Oxford historian Robert Gerwarth, working from Dublin, has recently argued that, in relative terms, Bulgaria was punished harder than the Weimar republic (Gerwarth 2021, p. 921). As part of the Paris treaties, the Treaty of Neuilly was imposed in November 1919. On the 19th of this month, the United States Senate refused to ratify the Treaty and League of Versailles. This argument may be right on the premise that assets such as Weimar's merchant fleet, exclusion respectively inclusion on a par in a thus aborted international organisation and the guilt lies about this nation, one colonial at the beginning of the Paris conference and the familiar one about 1914 at the end are being ignored (p. 218).