Multidimensional assault on Weimar and Waziri

A remote detail? While the British and nationalist Empire forces took the Entente and would-be League in their Winter-1919 endeavour in Paris to put themselves altogether on moral high ground, the facts on the ground in both Asia and Africa told a different story. Here's the case of Afghanistan 1923.

In this author's essay 'Sleepwalkers in Defiance of a Wake-up Call that Clark's Did Not Have' (2024), a biographical note on his German family refers to Dresden's destruction at the end of the Second World War. At the beginning of this war, the Luftwaffe wiped out a major part of Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and Coventry, England.

Shortly after the First World War, that saw the introduction of warfare's aerial dimension, the new weapon would be deployed against colonised people. At first sight, it appears as an 'internal conflict' between rebellious natives and the British Empire. However, the leadership of this largest empire overseas designed a postwar order that implicated the fixation of an international and triangular relationship. Who was the third party?

As described in in another chapter of this anthology, both Africans and Asians were confronted with a bombardment by the airforce of the principal authors of the Peace Treaty of Versailles, particularly its colonial articles. In Paris and its suburban residence, the League of Nations was founded. Ahead of all other issues, the treaty opened with this novelty. A central task of this organisation was to safeguard the interest of the native populations in the colonies. Its Permanent Mandates Commission was installed to monitor this internationalised rule that was introduced by the indispensable United States delegation, led by Woodrow Wilson. This meant that mandate powers took over the administration in enemy territories. Three gradations of British, British South African, British New Zealand's, British Australian, French, Belgian and Japanese rule were applied to the Turkish territories in Asia Minor and the German colonies. Should the colonised be treated inhumanely, the League was supposed to hold the motherland accountable. Obviously, none of the colonies, including the native inhabitants of their own, could be ruled out. In the post-war order, all the natives should be better off.

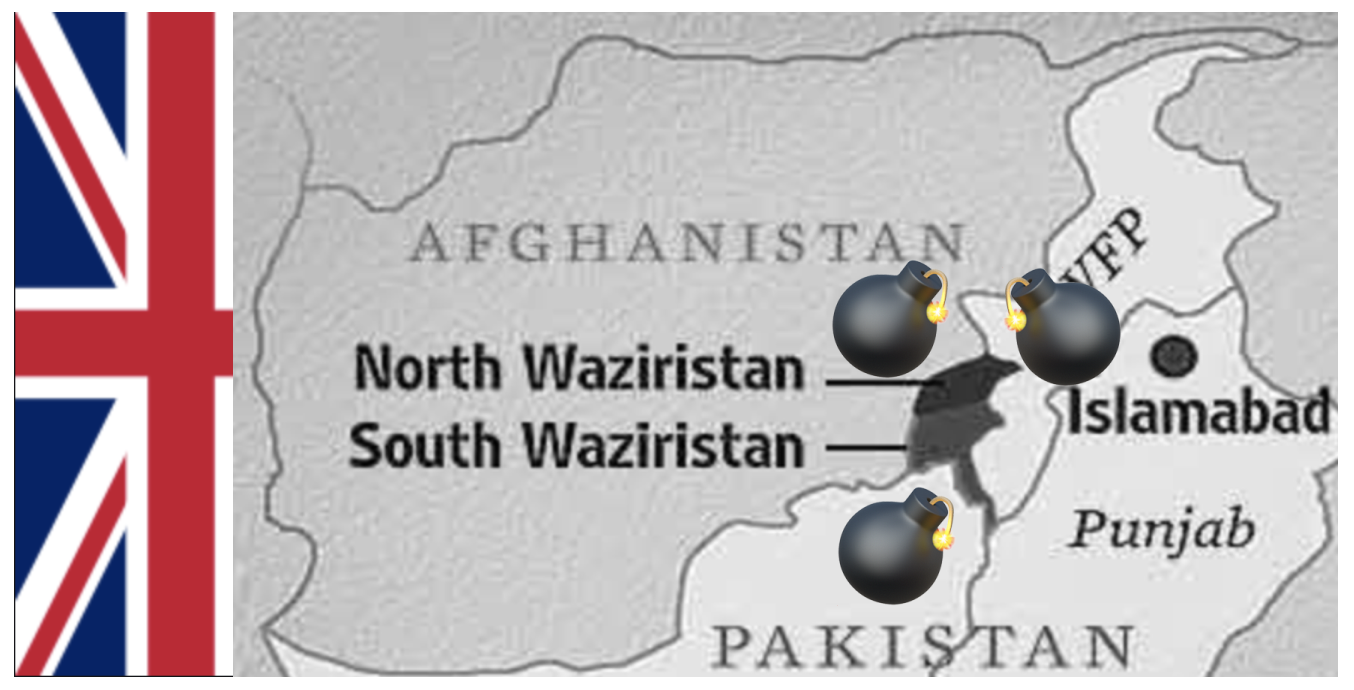

In the British colony of Afghanistan, the Waziri tribe took to resistance. On 23 June 1923, the Manchester Guardian reported that this tribe in the former colony – most notably independent through the Anglo-Afghan Treaty of August 1919 – was bombed by the Royal Airforce.(1)

As a consequence, the critique of 'double standards' would apply. Imagine the news's reception among a people that was deemed colonially inferior because of inhumane treatment. Whether she liked it or not, the Weimar Republic represented the third party.

During the three-times prolonged Armistice (1918–1919), Germany was decolonised. Not one, but two British delegations in Paris masterminded this decolonisation avant la lettre. Against all odds, this change of course in defiance of the Armistice Agreement precipitated the demise of imperialism. Independence movements would soon threaten to challenge the European master. For the first time, the colonised and a potential master would share a basic interest. For Asians, Africans as well as Germans, it ended up with sharing the role of bystander, if not unsuccessful applicant in Geneva. Until the demise of the Weimar Republic, the position of the League's Secretary General was occupied by Great Britain, the great diktat's and new order's principal designer.

By Germany's declassification on the argument of failing fitness for the civilising mission, the League, its leaders as well as any other member states were deemed to rule in the natives' interest. The opposite came true, which legitimated disparate claims for a substantial revision of the peace settlements in and out of Europe. From Asia to Africa, coloured people were bombarded by the RAF, before the Permanent Mandates Commission even held its third annual meeting.(2)

Peter de Bourgraaf

Footnotes

1. Sean Andrew Wempe, The Revenants of the German Empire. Colonial Germans, Imperialism, & the League of Nations, Oxford 2019, p. 49.

2. Robert Gerwarth and Erez Manela, Introduction, in: Gerwarth and Manela, Empires at War. 1911–1923, Oxford 2014, p. 13.